In surface-mount technology (SMT) production, tape splicing is a routine operation that directly influences feeder reliability, placement accuracy, and overall line uptime. Two primary methods are used in modern assembly environments: standard splicing and flying splicing. While both techniques serve the same functional purpose—joining two carrier tapes—the mechanical, operational, and risk profiles of each method differ substantially.

Understanding the differences between flying splice and standard splice is critical for manufacturing engineers, process technicians, and production managers who are balancing throughput targets with defect control and equipment protection.

A standard splice is performed when the SMT line is stopped or when the feeder is removed from the machine. The operator prepares the splice offline or at a workstation, ensuring precise alignment of the carrier tape pockets, cover tape, and sprocket holes before reloading the feeder. This method prioritizes mechanical stability and repeatability.

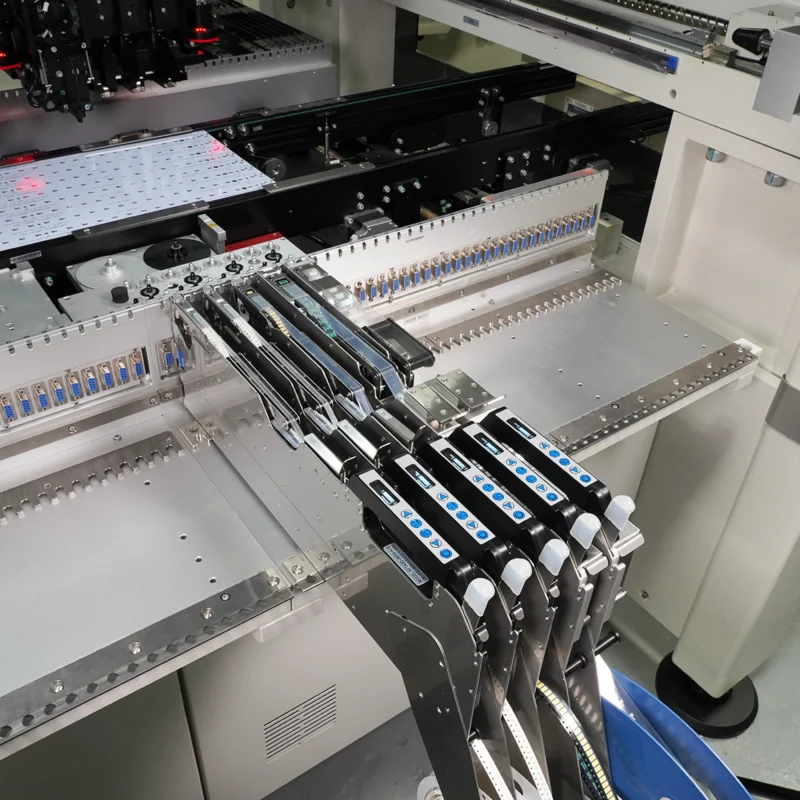

A flying splice, by contrast, is performed while the feeder continues to advance tape during production. The trailing end of the depleted tape is joined to the leading end of a new reel without stopping the machine. This approach is designed to eliminate downtime associated with reel changes, particularly in high-volume or time-sensitive production environments.

The key mechanical distinction lies in motion control. Standard splicing occurs in a static condition, allowing full control over alignment and tape geometry. Flying splicing occurs under dynamic conditions, where tape tension, feeder indexing speed, and operator timing all influence the final splice quality.

Flying splice is most commonly used in environments where:

In these scenarios, the operational benefit is clear: avoiding machine stoppage preserves throughput and reduces the cumulative impact of frequent reel changes. For commodity components used in large quantities—such as resistors, capacitors, or connectors—flying splice can be an effective strategy.

However, operational viability does not equate to universal suitability. Flying splice introduces constraints that do not exist in standard splicing, particularly related to alignment tolerances and tape thickness control.

Alignment tolerance is the most critical technical requirement for successful flying splicing.

During a standard splice, the operator can visually and mechanically ensure that:

Flying splice significantly reduces the margin for correction. The tape is already moving, and the feeder mechanism continues indexing based on expected pitch values. Even a minor misalignment can compound over several advances, resulting in gradual pocket offset, component skew within the pocket, or misregistration at the pick location.

High-speed feeders are particularly sensitive to alignment deviation. At typical SMT line speeds, the feeder does not have time to compensate for geometric inconsistencies introduced at the splice point.

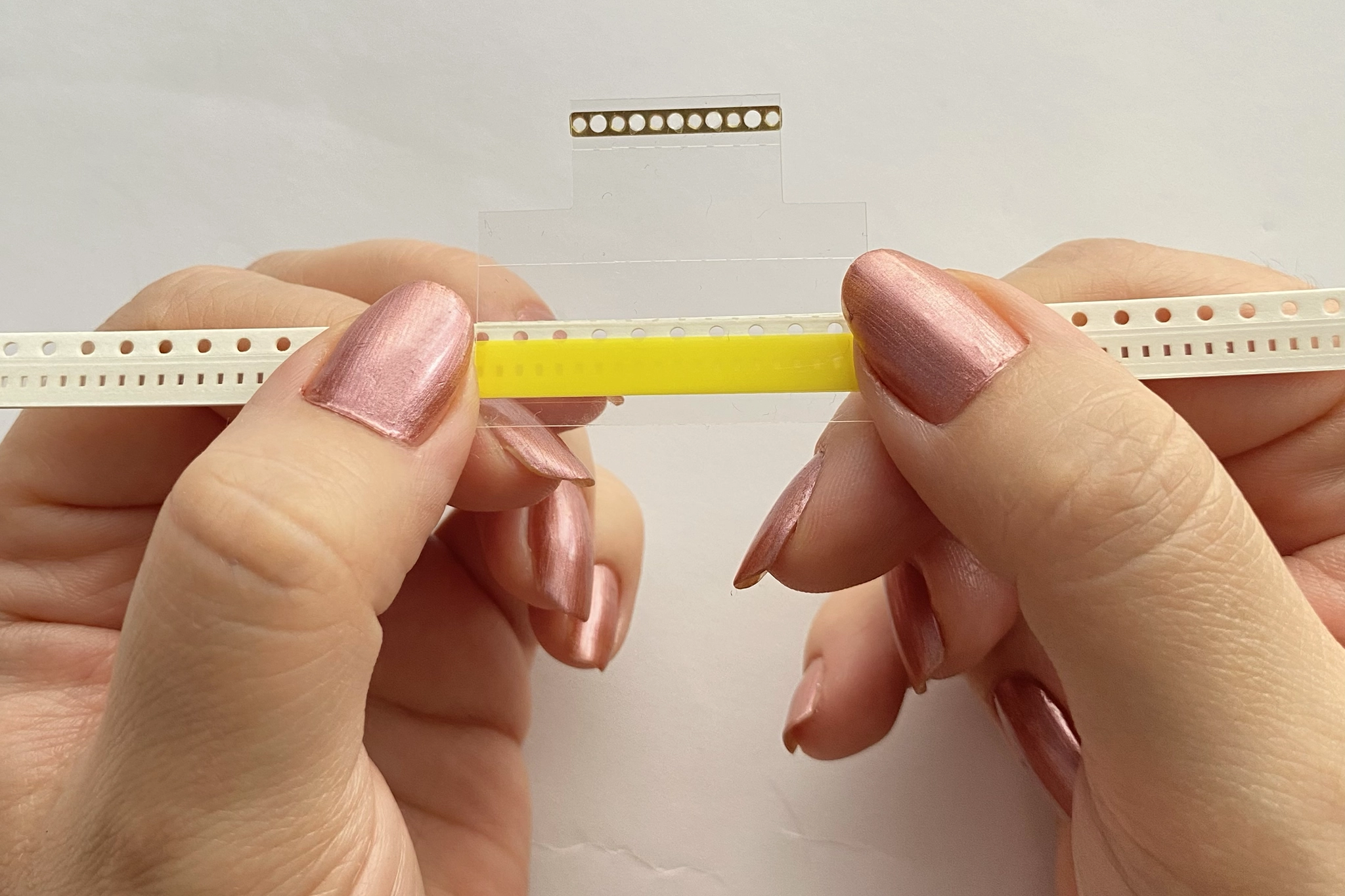

Precision splice tools play a central role here. Tools designed with fixed guides, hardened alignment pins, and controlled cutting geometry reduce the variability introduced during flying splicing. Without such tooling, flying splice alignment relies heavily on operator dexterity, which increases process risk.

Tape thickness becomes a critical factor when evaluating flying splice reliability.

At the splice point, total thickness increases due to the overlap of carrier tape, splice tape adhesive, and the cover tape junction.

In standard splicing, excess thickness can often be visually inspected and corrected before the feeder is reinstalled. In flying splice operations, this verification step is eliminated.

Modern feeders rely on optical, mechanical, or capacitive sensors to detect tape presence, pocket pitch, and indexing position. A localized increase in thickness can interfere with sensor readings, leading to false tape-end detection, skipped indexing steps, or feeder stoppages triggered by error states.

Modern feeders rely on optical, mechanical, or capacitive sensors to detect tape presence, pocket pitch, and indexing position. A localized increase in thickness can interfere with sensor readings, leading to false tape-end detection, skipped indexing steps, or feeder stoppages triggered by error states.

Double splice tapes engineered with controlled adhesive thickness are specifically designed to minimize thickness stack-up. This becomes especially important in flying splice scenarios, where sensor interaction occurs immediately after the splice passes through the detection zone.

Consistent tape thickness is not only a materials issue but also a process issue. Uneven pressure during splice application can create localized high points that amplify sensor interference.

Flying splice introduces a set of risk factors that do not exist in standard splicing, particularly when performed at full production speed.

These risks increase as line speed increases. What may be a tolerable deviation at lower speeds can become a defect trigger at high-speed placement rates.

Repeated exposure to excessive splice thickness affects not only immediate placement accuracy but also long-term feeder health.

As splices pass through feeder mechanisms, excess thickness can cause accelerated wear on guide rails, increased friction on indexing wheels, and deformation of cover tape peel mechanisms.

Over time, this leads to feeders becoming more sensitive to any splice irregularity, even those within nominal tolerances. In high-throughput environments, this cumulative effect contributes to higher feeder maintenance costs and reduced equipment lifespan.

Using splice tapes with tightly controlled material specifications mitigates this effect, particularly when flying splice is part of the standard operating procedure.

Standard splicing remains the preferred method in environments where high-reliability assemblies are produced, fine-pitch or sensitive components are used, ESD exposure must be tightly controlled, and traceability and repeatability are prioritized.

By stopping the line or preparing splices offline, operators gain full control over alignment, pressure, and inspection. This method reduces dependency on operator timing and minimizes mechanical variability at the splice interface.

Standard splice also integrates more effectively with documented process controls and quality audits, making it common in aerospace, defense, and medical electronics manufacturing.

Flying splice and standard splice are not competing techniques so much as context-dependent tools. The decision should be based on component criticality, feeder sensitivity, line speed, operator skill level, and quality risk tolerance.

Production environments that attempt to apply flying splice universally—without considering these variables—often experience inconsistent results.

Splice tooling and materials selection play a decisive role in whether flying splice can be executed reliably. Precision-guided tools, controlled-thickness splice tapes, and standardized procedures reduce variability and support higher success rates.

Flying splice places greater demands on both tools and consumables. Precision tape splicer tools provide fixed alignment references, repeatable cut geometry, and controlled overlap zones.

Similarly, high-quality splice tapes engineered for SMT applications ensure uniform adhesive thickness, stable carrier backing, and predictable sensor interaction.

When flying splice is executed without these controls, it effectively shifts process risk from downtime to quality defects and feeder errors.