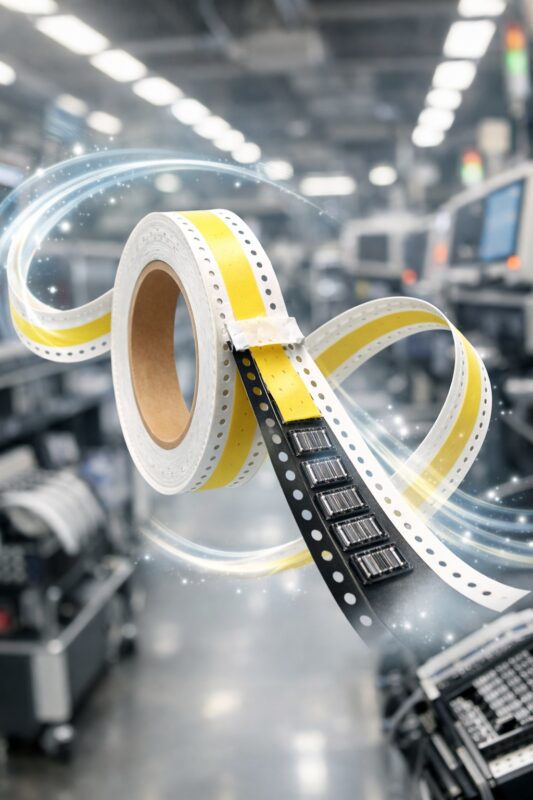

Flying Splice Tape in Modern SMT Assembly

In modern SMT assembly, downtime is the enemy. Lines routinely run at 30,000–40,000+ components per hour, feeders are tightly synchronized, and any pause ripples downstream into lost throughput, scrap risk, and missed delivery windows. That’s where flying splice tape comes in.

A flying splice is exactly what it sounds like:

a reel-to-reel splice performed while the SMT line continues running at full speed—no feeder stop, no placement pause, no head deceleration.

This is not a marketing term. It’s a mechanical and materials engineering problem that only a small subset of splice tapes are designed to survive.

What Makes a Splice “Flying” in SMT?

A traditional splice assumes:

- The feeder is stopped

- Tape tension is static

- The splice sees low dynamic load

A flying splice assumes the opposite.

During a live reel changeover, the splice must endure:

- Instantaneous acceleration

- Continuous peel force

- High-frequency indexing

- Shear stress at sprocket engagement

- Vacuum pick forces at the pocket level

All of this happens while the splice is being pulled through the feeder, indexed by the sprocket wheel, and presented to the placement head without missing a beat.

If the splice fails, the line doesn’t gently slow down. It rips, jams, or misfeeds at speed.

The Physics of a Flying Splice

At high CPH rates, a splice experiences a unique combination of forces:

1. Tensile Load Under Constant Velocity

The splice is under continuous tension as the feeder advances the tape. Any weak adhesive bond or thin carrier film elongates, creeps, or snaps.

2. Shear at the Adhesive Interface

Unlike static splices, flying splices see shear loading, not just peel. This is where many low-cost splice tapes fail, especially those optimized only for peel strength.

3. Sprocket Shock Loading

Each index introduces a micro-impact at the sprocket holes. If the splice bridges poorly across sprocket holes, tearing starts here first.

4. Placement Head Vacuum Events

When the splice passes under the nozzle, airflow and vacuum transitions can momentarily flex the carrier tape, another stress event cheap tapes never account for.

Why Most SMT Splice Tapes Fail at Flying Speeds

Many splice tapes on the market were designed decades ago for:

- Slower feeders

- Manual reel swaps

- Intermittent placement

They rely on:

- Thin polyester backings

- Generic acrylic adhesives

- Minimal overlap geometry

At modern speeds, these tapes exhibit:

- Adhesive creep

- Carrier delamination

- Pocket distortion

- Sprocket hole tearing

- Complete splice separation mid-run

That’s why operators often think they are doing flying splices until the first catastrophic failure teaches them otherwise.

What Defines a True Flying Splice Tape

A flying splice tape is engineered differently, not branded differently.

A flying splice tape is engineered differently, not branded differently.

High-Shear Adhesive System

The adhesive must resist lateral movement, not just vertical peel. This typically means a higher-modulus adhesive tuned for dynamic load.

Reinforced Carrier Backing

The backing film must survive repeated indexing impacts without elongation. Thickness alone is not enough, film stability matters more than raw mils.

Controlled Overlap Geometry

Flying splices depend on consistent overlap length to distribute stress evenly across the joint. Short overlaps concentrate load and fail early.

Sprocket-Safe Design

The splice must bridge sprocket holes cleanly without weakening the pitch accuracy of the carrier tape.

Operator Skill Still Matters

Even with the right tape, flying splices are a discipline.

Experienced SMT operators manage:

- Proper tape alignment

- Clean cut edges

- Correct overlap placement

- Consistent splice pressure

At full line speed, there is zero margin for sloppy execution. Flying splicing is closer to motorsports pit work than bench assembly, fast, precise, repeatable.

Why Flying Splices Are Becoming Mandatory, Not Optional

As SMT lines push:

- Higher CPH targets

- Smaller components (0201, 01005)

- Tighter feeder tolerances

Stopping a line for reel changeovers becomes economically irrational.

Flying splices:

- Preserve takt time

- Reduce feeder wear from stop-start cycles

- Eliminate restart scrap

- Improve overall equipment effectiveness (OEE)

In high-mix, high-volume environments, they are no longer a “nice to have.” They are a process requirement.

The Bottom Line

A flying splice is not just a splice done quickly.

It is a splice that survives continuous motion, dynamic load, and mechanical shock all at production speed.

If your splice tape was not explicitly designed for:

- High shear

- Dynamic tension

- Full-speed indexing

Then what you are doing is not a flying splice.

It’s just a gamble that hasn’t failed yet.

In modern SMT assembly, real flying splices don’t slow the line down.

They disappear into it quietly, invisibly, and without mercy for weak materials.